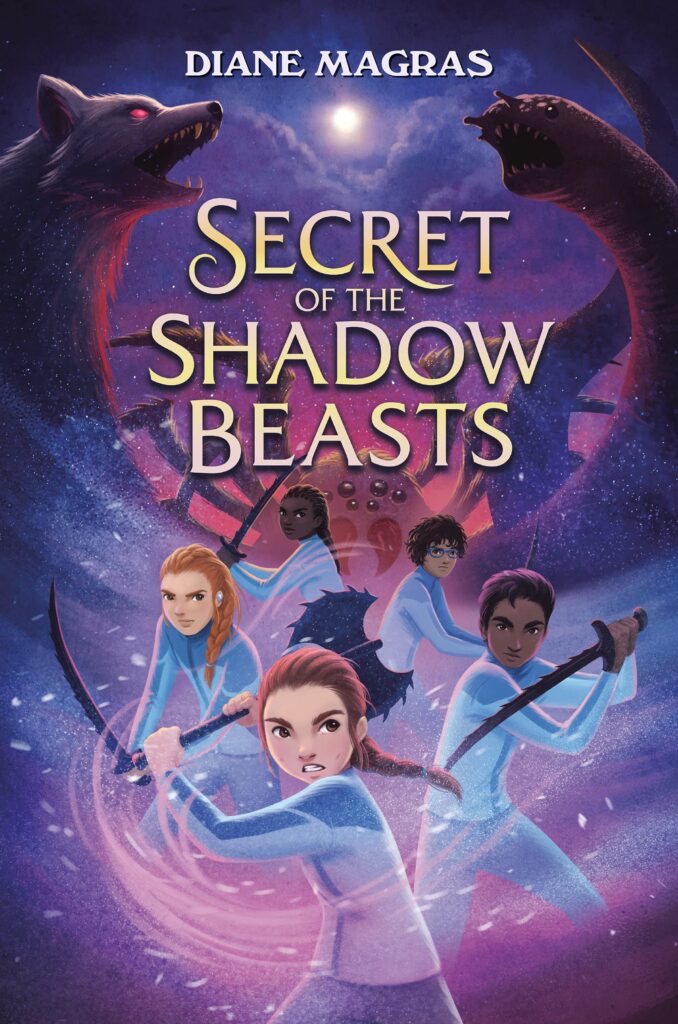

When Nora and her mom have a close encounter with shadow beasts, deadly creatures like the ones who killed her father years ago, she vows to do something to help eradicate them from her homeland of Brannland. When she was younger she was identified as a potential knight, someone immune to the bite of the beasts until she became an adult. But her father wouldn’t let her train in the elite corps that helps to eradicate them. Now 12, Nora decides the time to fight has come. The question is, will the knights still want her?

Secret of the Shadow Beasts is a fast-moving adventure tale that will have young readers turning pages anxious to see what happens next. Nora has heart and courage as well as natural ability, all characteristics she needs to fit in with the other knights who have been training for years. Throughout the story she learns about herself and what she’s capable of. She also learns more about her dad and why he wanted to keep her from joining the knights. There’s an underlying message about caring for the Earth and the lasting effects of pollution.

I recommend Secret of the Shadow Beasts for readers aged 9 to 12.

The publisher provided me with a copy of this title in exchange for my honest review.