Today I’m featuring a review of Operation Oleander with a giveaway of one copy to a reader in the U.S. or Canada.

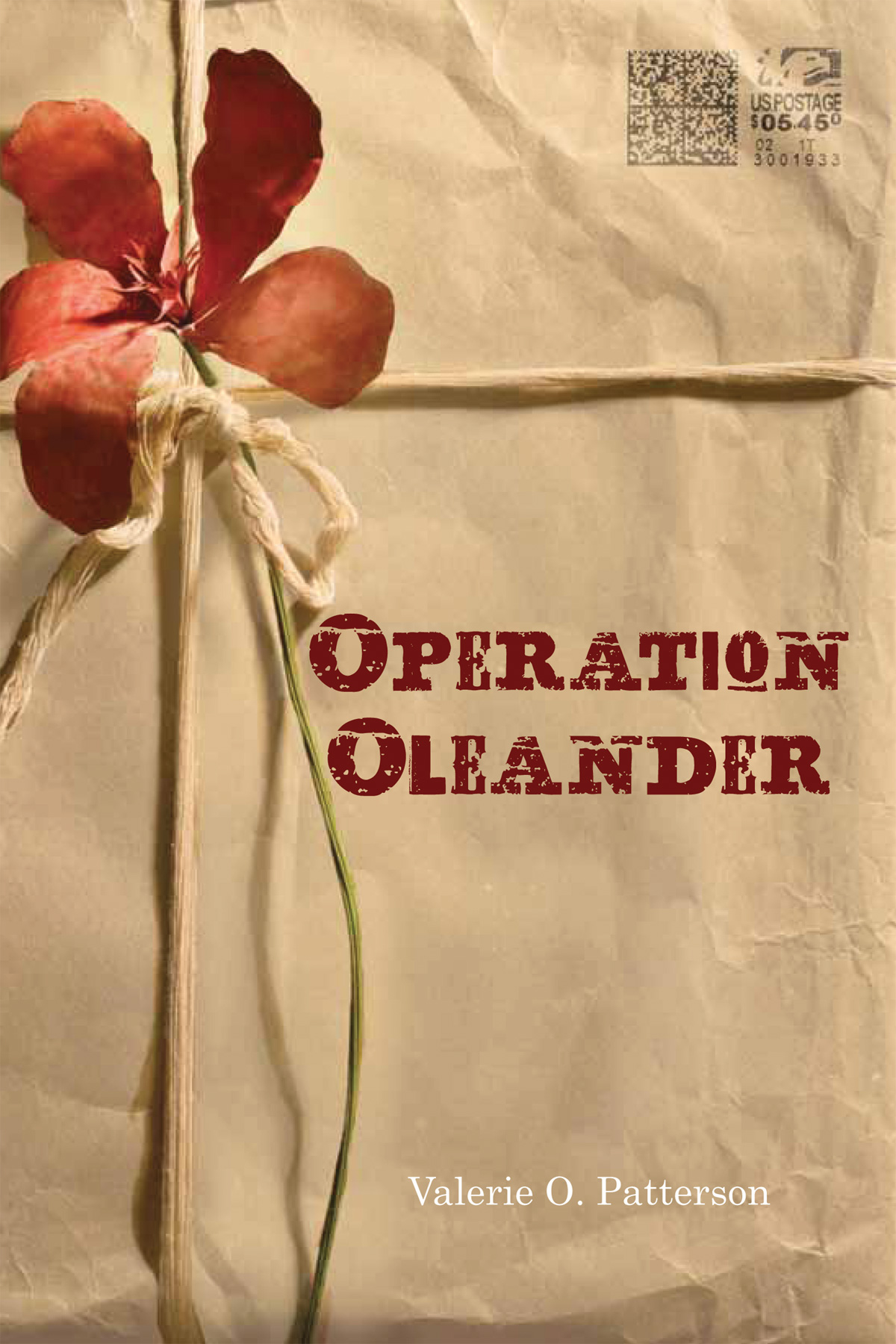

Today I’m featuring a review of Operation Oleander with a giveaway of one copy to a reader in the U.S. or Canada. Just leave a comment by midnight (PDT) Monday, March 18 for a chance to win. (Please note: the giveaway is closed. Congratulations to Kismet on winning.) Check back tomorrow when author Valerie O. Patterson shares with us information on her writing life as well as some of the issues raised in the book. Here’s my review:

Jess feels good about the school supplies she and her friends, Meriwether and Sam, have been collecting for an orphanage in Afghanistan. Her dad and Meriwether’s mom are both deployed there, and Jess feels doing something to help the orphans lets her feel close to her dad while he’s gone.

But when the troops stop off to deliver supplies one day, a bomb goes off, killing some of the orphans and Meriwether’s mom. Jess’s dad is badly injured. Suddenly the troops’ involvement in the local civilian problems doesn’t seem like such a good idea. Jess struggles with the guilt she feels at the same time she becomes more determined than ever to help the children in Afghanistan.

Operation Oleander by Valerie O. Patterson highlights issues from the war in Afghanistan in a way that kids can relate to. Jess was adopted by her parents when she was younger, so she feels particularly connected to the orphans, especially to a girl named Warda who her dad has sent photos of. The issue of whether U.S. soldiers can play a humanitarian role as well as a military one in the countries where they are deployed is interesting to consider.

Jess struggles to do the right thing, but not everyone agrees on what the right thing is. She’s also wondering how she can support Meriwether, who has just lost her mother, especially when she’s worried about her dad and his recovery. The issues Jess faces, and the way she decides to deal with them, should lead to interesting discussions in mother-daughter book clubs with girls aged 9 to 13.

The author gave me a copy of this book in exchange for my honest review.