Deborah A. Levine and JillEllyn Riley are the authors of The Saturday Cooking Club, a great series of books for young readers (see my review). They are stopping in at MotherDaughterBookClub. com today to talk about cooking with mom and to share a recipe for easy fudge. My daughter loves chocolate (so do I!), but fudge is her particular favorite, so we were both excited to try it out. Read on to find out what the authors have to say and to get that recipe.

From Deborah A. Levine and JillEllyn Riley

Much of the action in our middle-grade series, The Saturday Cooking Club, takes place in a weekly cooking class taken by our three main characters and their moms. With all that mother-daughter time in the kitchen, it didn’t surprise us that one of first questions most people asked us was whether we were inspired by memories of cooking with our own mothers. What did surprise us (at least the first time) was that neither of us had ever given it much thought–and when we did, we both came up with a resounding, “Not really.” That said, we each have memories of our mothers that are deeply linked to food–and as much a part of who we are today as any treasured family recipe.

Deborah A. Levine

My mother made the majority of the breakfasts, lunches, and dinners in our house when I was growing up, but I have always had a rather “quirky” palate. For much of my childhood, I was the kind of kid who thought whatever my friends’ parents served up was infinitely more glamorous than anything my mom would make–even if all they did was heat up a box of fish sticks (we never had those in our freezer!). As a teenager, I was usually on some weird diet or another and generally shunned anything that didn’t fit into its bizarre perameters (bananas and milk, anyone?). The one constant in my fickle relationship with food, however, is vegetables (ok, and sugar–but that’s a given). I’ve always loved pretty much anything green and crunchy, and lucky for me, my mother is an expert gardener.

My mother’s garden bordered three sides of our backyard. It wasn’t huge, and in many places the veggies were mixed in with the flowers, but each spring I looked forward to discovering which of my favorites would be popping up between the roses or next to the peonies. There were always tomatoes, a family staple, and usually bell peppers, too. I remember being fascinated by the way the cucumber and squash vines twisted around the slats of our rickety old wooden fence, and how such long, heavy vegetables started out as tiny green fingers poking out of the flowers. I loved to harvest everything, but the peas and beans were my favorites (and still are). On a good day at the height of the season, you could fill a bucket with them and still pick a handful for snacking.

Today my mother lives in Miami and has mango and papaya trees in her garden, instead of bush beans and cucumber vines. I live in an apartment without a yard or even a patio–but I do have a small plot in a community garden a few blocks away. I don’t have my mom’s green thumb or encyclopedic knowledge of plants, but I still look forward every year to filling my patch of soil with as many crunchy green things as I can squeeze in. This year, I’m growing tomatoes, peas, beans, squash, and cucumbers, just like my mom always did. I sent her a picture as soon as I planted them–and my kids and I already can’t wait to get picking.

JillEllyn Riley

I never really cooked with my mother. I mean, she cooked dinner when we were kids, but she cooked dinner because dinner needed to be cooked. She did not relish her time in the kitchen or use it as a creative outlet–she was a busy, trailblazing newspaper woman who happened to have kids. Dinner was a necessity. As soon as we could read recipes, my mother assigned each of us our own “dinner night.” As we were learning, we may have eaten Jello and undercooked homemade French fries, but it meant we helped out with the dinner burden and that was what mattered.

Our extended family has an ingrained tradition of demonstrating love through food, though, so there was definitely a prevailing sense of the specialness of our family recipes. My sister and I took over the baking traditions early on. As small children, we could cream butter like professionals and don’t even get me started on our dicing skills. There are mishaps when little people use a stove or an electric mixer, but only once was the situation scary enough to require a roaring, racing fire truck. I have since perfected my grandmother’s easy fudge.

With my own children, we continue making cherished recipes as well as pioneering our own. Like my mother, I cook dinner because dinner needs to be cooked. And I do pull in both my boys to help make it happen. One of them is a tremendous sous chef–he can prepare ingredients (measuring & mixing, sifting & chopping) so that I can effortlessly put it all together like the star of a cooking show. The other fellow likes to mix it up in the kitchen, scrambling eggs with cinnamon or making mini-pizzas on biscuit dough. There are many ways of cooking as a family, sharing the tasty, the traditional, and occasionally the burned. Whatever it is, we all have to eat it together!

In case anyone wants to try a family favorite, here is Nana Brown’s recipe for Easy Fudge.

Easy Fudge

Melt in a double boiler: 3 cups of chocolate chips

Add:

1 can of Eagle Brand sweetened condensed milk

A pinch of salt

2 teaspoons of vanilla

Mix in 1/2 cup chopped walnuts, if desired

Pour at once into a slightly oiled 8 x 8 or 9 x 9 pan, before it hardens. Cool before cutting.

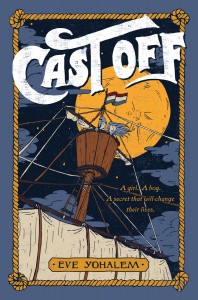

To escape her abusive father, a wealthy Amsterdam merchant, Petra de Winter seeks refuge on a ship setting sail to the East Indies. She fears dire consequences when Bram Broen, the ship’s carpenter’s son, finds her. Instead, together they come up with a plan that will help Petra escape and Bram find favor with the captain. As they sail they find adventure in fending off pirates, weathering storms, and navigating a mutiny.

To escape her abusive father, a wealthy Amsterdam merchant, Petra de Winter seeks refuge on a ship setting sail to the East Indies. She fears dire consequences when Bram Broen, the ship’s carpenter’s son, finds her. Instead, together they come up with a plan that will help Petra escape and Bram find favor with the captain. As they sail they find adventure in fending off pirates, weathering storms, and navigating a mutiny.