Author Shana Burg with villagers in Malawi

Yesterday I reviewed a new book by Shana Burg called Laugh with the Moon. Burg has also won awards for a previous book, A Thousand Never Evers, which looks at the civil rights movement in the U.S. Today, I’m featuring an interview with the author.

Why did you decide to become a writer?

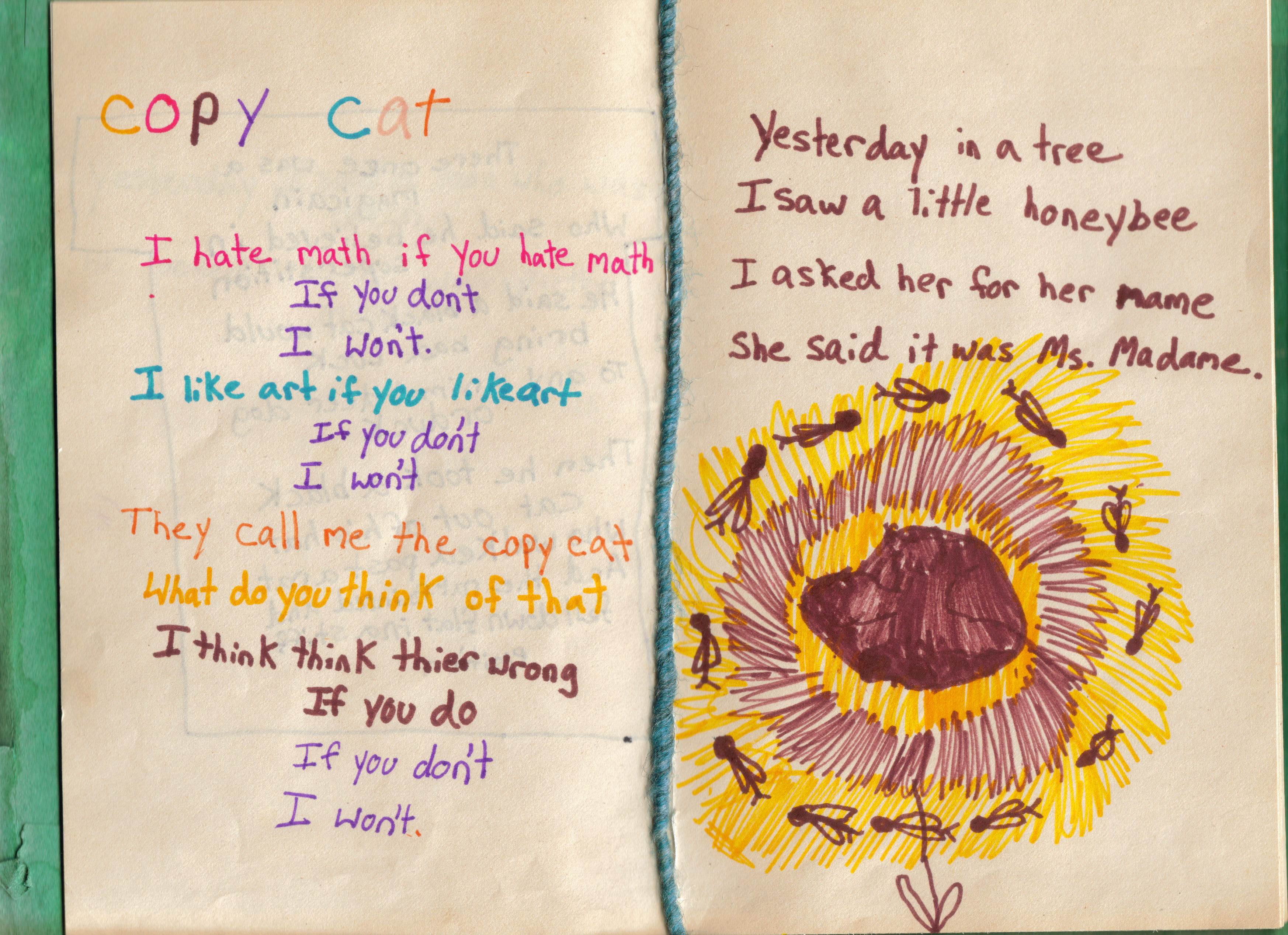

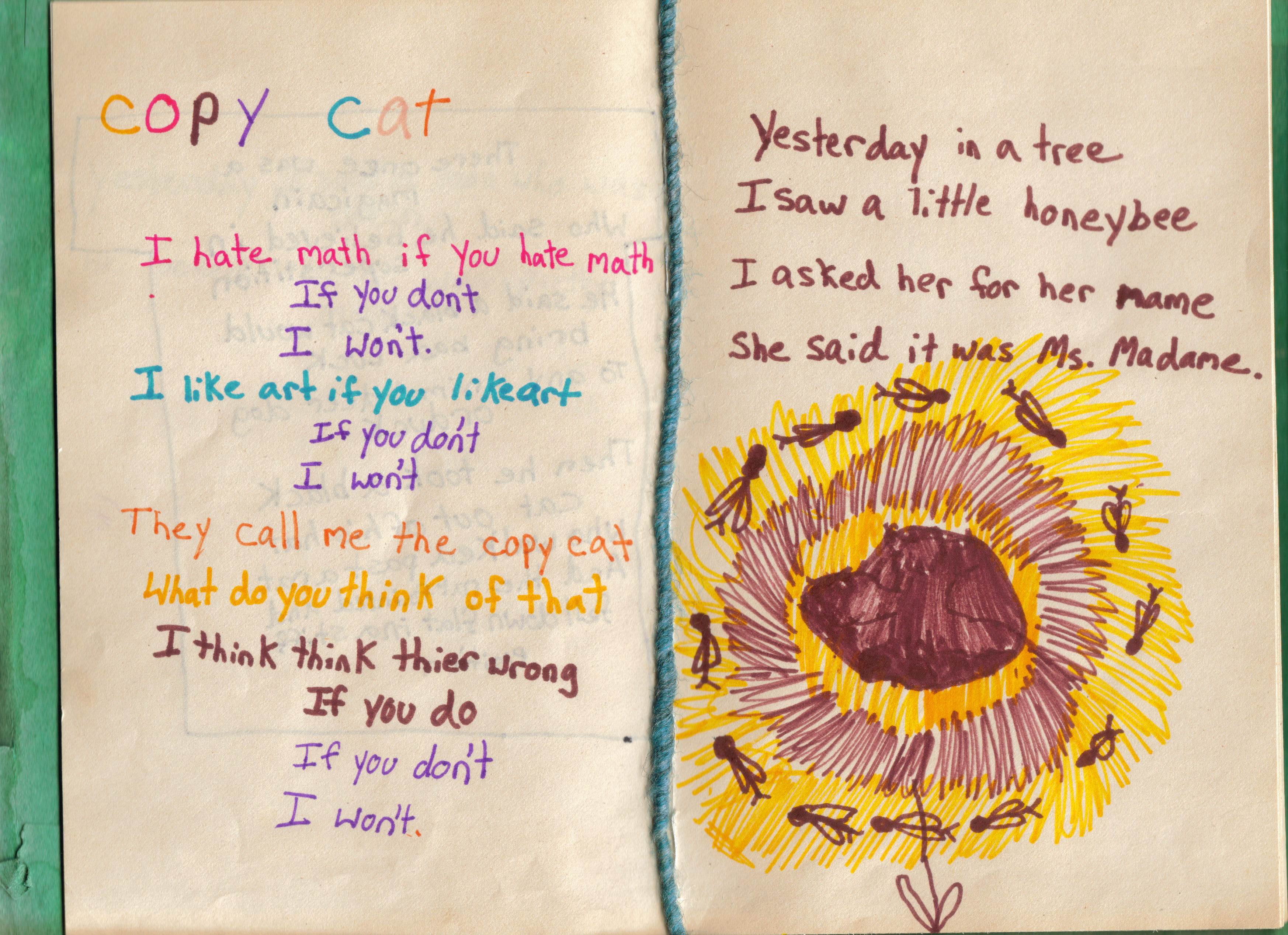

SB: I was in fourth grade and my teacher assigned us to create an original book of poems. As soon as I started working on mine, I was hooked! The next year, I had the same teacher and she let me start a classroom newspaper called The Razzling Dazzling Room Review. I’ve been writing ever since. (Here’s a photo of one of Shana’s early poems.)

What do you like most about writing books for children?

SB: My husband says that I’m a tween stuck in a grown-up body. I think that he may be right. While I can’t remember what I ate for dinner last night, I seem to remember my tween years in Technicolor. That’s probably why I ended up teaching sixth grade, and why I’ve had many jobs working with kids of all ages. What I like most about writing books for young readers is that they are usually more open to new ideas and adventures than adults—no offense, adults!

What do you think is the most challenging aspect of writing?

SB: The hardest thing about writing is moving what’s in my mind to the blank page. I discovered this flaw of mine the first time I met with my editor, the amazing Michelle Poploff. During this meeting at Random House in New York, Michelle asked me lots of questions about my first book, A Thousand Never Evers. It was still a manuscript at that point. She said, “Why does Addie Ann do this? How does the garden get ruined?” And I said, “Oh, I explained that in the story. You must have missed it. That’s on page…page oops! Guess I didn’t explain it after all, he he.” I was so familiar with the characters and story in my imagination that it was hard to be sure that everything in my mind actually wound up on the page.

I understand you spent some time at schools in Africa. What about that experience stayed with you and prompted a book that takes place in Malawi?

SB: I was truly flabbergasted by how the students and teachers I visited in Malawi were able to accomplish so much with so few resources. I mean, literally, I saw roofs that had blown off of classrooms in the rain, classes of 200 standard one (first year) students and only one teacher, and teachers who couldn’t find a single piece of paper to write on. Can you imagine! Still, these teachers and students had devised creative ways to learn. I wrote about many of these innovative methods in Laugh with the Moon.

Clare sees that what may be a small amount of money to her is huge for the villagers she lives among. Yet she knows she can’t just give money to help when problems arise. Why is that?

SB: Giving money is a short-term, band-aid solution. While it may help someone in need, it won’t necessarily provide a long-term fix. Let me give you an example. When I was in Malawi in 1997, I visited a warehouse that stored books that had been donated by people who lived in wealthy nations like the U.S. and Australia. The problem was that those books had been sitting in the warehouse for years and years! The books were just sitting there when, say, fifty miles away the students had no books at all.

Why did that happen? Well, the Government of Malawi had very few trucks to use to distribute the books to the schools, and the drivers of the trucks didn’t have money for fuel. And even if they had money for fuel, all of the schools that needed books weren’t on the maps so the drivers wouldn’t know how to reach them.

This taught me that people who want to help always should do research to make sure that their donations are going to address the problem. In this case, the people who sent books probably should have investigated whether there was a proven way for them to reach the children who needed the books in a timely fashion.

Clare wonders how her friend Memory can go on with life when so many sad things have come her way. What do you think contributes to Memory’s resiliency?

SB: What a great question! I think Memory copes, first and foremost, because she must. Her little brother is relying on her, and her grandmother is too. Someone has to fetch the water, sweep the hut, cook the food.

Also, in Malawi where Memory lives, kids who have lost their parents are a dime a dozen. This fact doesn’t make the loss hurt any less, but it does provide more role models who are managing their lives with grief. And it really is true what Mrs. Bwanali tells Clare: The child that belongs to my neighbor also belongs to me. In Malawi, frequently the village comes together to raise and support children who are orphaned.

If book clubs want to help schools in Africa, are there organizations you recommend they work with?

SB: I highly recommend two organizations that work with students in Malawi, Africa:

First, World Altering Medicine provides free medical care to children who would likely die from malaria and pneumonia without their help. They also run a secondary school, where tweens and teens learn to read and write English by corresponding with pen pals. There are many ways for youth to partner with World Altering Medicine to save and improve lives halfway around the world. For more information, contact Sarah Greenberg: sarah@worldalteringmedicine.org. You may also be interested in viewing this video on YouTube.

I also recommend K.I.N.D.—Kids in Need of Desks, a project that raises money to build desks for school children in Malawi. Can you imagine sitting on a dusty dirty floor all day? It’s very uncomfortable and hard to learn to read and write that way. Through this program, UNICEF volunteers work with local Malawians to build desks for students right near the schools where they are needed. $24 can provide one desk; $48 will provide a desk and bench for two students; a gift of $720 will furnish an entire class of 30. Call 1-800-367-5437 to donate.

In your book A Thousand Never Evers, you wrote about the civil rights movement. Why do you think it’s important to have books for children set in that era?

SB: The civil rights movement was an incredible time for our nation because young people literally rewrote the course of history. Yes, many were too young to vote, but they were not too young to act in ways that captivated the attention of the US President and news media around the world.

Children as young as six years old marched for equal rights in Birmingham, Alabama. Tweens and teens filled the jails by the hundreds to demand an end to the Jim Crow laws that legalized treating people of color as second-class citizens. I think kids these days need to know how much power they have. They don’t need to wait to be grownups to change the world–the civil rights movement proves it.

In my opinion, you do a great job of weaving a message into a story without preaching. Do you find that difficult, especially when writing about issues that may have emotional resonance with you in some way?

SB: Thank you very much. I know that my job as an author is to follow my characters through a story. When I’m editing my work, I make sure to delete any sentences that sound preachy or where I feel I’ve abandoned the journey of my characters and stepped onto a soapbox.

Is there anything else you would like to say to readers at Mother Daughter Book Club. com?

SB: No doubt the girls who read this are thinking, creative, smart, and dynamic people. I love knowing that they are exploring the world through literature alongside their moms, who surely have experienced so much and have incredible insights to share with their daughters. When moms and daughters put their minds together, they generate a powerful force—one that can probably solve a lot of the world’s most tricky and pressing problems. So I say, keep on reading, keep on thinking, and keep on working together to change the world!

For more information visit ShanaBurg.com. You can like her at www.facebook.com/shanaburgwrites and follow her on Twitter @ShanaBurgWrites.

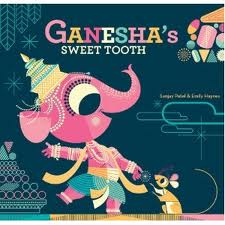

Ganesha is a Hindu god who can’t get enough sweets. His love of candy leads to tragedy when he breaks a tusk on a jawbreaker. Ganesha despairs about his strange looks until the poet Vyasa finds a purpose for the broken tusk: writing down the long story of the Mahabharata.

Ganesha is a Hindu god who can’t get enough sweets. His love of candy leads to tragedy when he breaks a tusk on a jawbreaker. Ganesha despairs about his strange looks until the poet Vyasa finds a purpose for the broken tusk: writing down the long story of the Mahabharata.