As the daughter of one of the Foundry’s top executives, 12-year-old Phoebe Plumm lives a privileged life in her mansion at the top of the hill. Despite the gadgets and baubles that make life easier for her, she is lonely. But her life takes a turn when she and her dad are kidnapped and the two of them are separated. With the help of Micah, a boy who works on her estate, she escapes and avoids recapture as the two of them go on a quest through a strange land to rescue her father, discovering a terrible secret about the Foundry along the way.

As the daughter of one of the Foundry’s top executives, 12-year-old Phoebe Plumm lives a privileged life in her mansion at the top of the hill. Despite the gadgets and baubles that make life easier for her, she is lonely. But her life takes a turn when she and her dad are kidnapped and the two of them are separated. With the help of Micah, a boy who works on her estate, she escapes and avoids recapture as the two of them go on a quest through a strange land to rescue her father, discovering a terrible secret about the Foundry along the way.

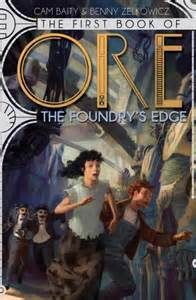

The First Book of Ore: The Foundry’s Edge takes readers into a world where machines are alive and humans are the intruders. Before they left home, Phoebe and Micah were enemies, playing mean pranks on each other. Their new environment, however, is harsh, and they need to trust each other if they hope to survive.

The Foundry’s Edge creates an alien world where the evil leaders of a powerful corporation exploit locals. As Phoebe and Micah escape from one danger after another, they are horrified to find out the truth of what happened behind the scenes of their comfortable lives. When the inevitable confrontation occurs, they have to pull on all their strengths, and their budding friendship, to survive.

This first book in the series takes readers on an adventure with a conclusion that will leave them eager to read the next installment. I recommend The Foundry’s Edge for ages 9 to 13.

The publisher provided me with a copy of this book in exchange for my honest review.