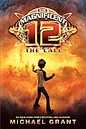

David MacAvoy—Mack for short—is an unlikely hero. He’s 12, picked on by bullies, and he has a phobia of nearly everything. Unexpectedly he finds himself under the protection of the school’s biggest bully and getting messages from strange old men who can stop time. Then he learns that he’s one of a group of 12 kids who are the only ones who can save the world from an evil queen who’s been imprisoned for thousands of years. It’s too much for Mack to believe, until many unbelievable things start to happen around him.

David MacAvoy—Mack for short—is an unlikely hero. He’s 12, picked on by bullies, and he has a phobia of nearly everything. Unexpectedly he finds himself under the protection of the school’s biggest bully and getting messages from strange old men who can stop time. Then he learns that he’s one of a group of 12 kids who are the only ones who can save the world from an evil queen who’s been imprisoned for thousands of years. It’s too much for Mack to believe, until many unbelievable things start to happen around him.

The Magnificent 12: The Call is the first in a new series for young readers by Michael Grant. Mack is an ordinary kid—just the sort of hero to appeal to both boys and girls aged 9 to 12. The book is funny, and it takes lots of jabs at modern society. For instance, Mack’s middle school (Richard Gere) offers advanced placement yoga and noncompetitive bowling among its electives. Bullies in his school are assigned to specific populations, so there are bullies for nerds, jocks, fashionistas and other clique groups.

An ancient language, a bit of magic and a touch of world travel all come into play as Mack goes about finding the next member of The Magnificent Twelve. I expect his journey will be fun to follow as it unfolds.